and Cladoendesis of Ephemeroptera. See also list of publications on

the principles of post-Linnaean nomenclature.

and Cladoendesis of Ephemeroptera. See also list of publications on

the principles of post-Linnaean nomenclature.| principles of systematics and nomenclature | general system and phylogeny of insects | systematics of Ephemeroptera |

| last update 16.V.2022 |

PRINCIPLES OF NOMENCLATURE

of

ZOOLOGICAL TAXA

|

The division I.3. from the book by N. Kluge |

Besides known data, this division

contains new rules which allow to

bring in order usage of all published Latin zoological names. The new system of

nomenclatures suggested here, includes the International Code of Zoological

Nomenclature as a part. As an example of usage of rank-free

nomenclature for taxa traditionally attributed to family- and genus-groups, see "The Phylogenetic System of

Ephemeroptera"  and Cladoendesis of Ephemeroptera. See also list of publications on

the principles of post-Linnaean nomenclature.

and Cladoendesis of Ephemeroptera. See also list of publications on

the principles of post-Linnaean nomenclature.

![]() I.5. Principles of classification of supraspecies taxa

I.5. Principles of classification of supraspecies taxa

![]() I.6. Principles of nomenclature of taxa

I.6. Principles of nomenclature of taxa

* Why do we need rules of nomenclature?

* Independence of taxonomy from nomenclature

I.6.1 General principles of nomenclatures of biological taxa

I.6.1.1 Availability and validity of names

I.6.1.2 Principle of priority

I.6.2 Different types of nomenclatures and names

* Why do different types of nomenclature coexist?

* Rank-based (ranking) nomenclatures

* Circumscription-based (circumscriptional) nomenclatures

* Description-based nomenclatures

* Phylogeny-based (phylogenetic) nomenclatures

* Hierarchy-based (hierarchical) nomenclatures

I.6.3 Rank-based (ranking) nomenclatures

I.6.3.1 Names regulated by the International Code of Zoological Nomencature (ICZN)

I.6.3.1.1 Historical

I.6.3.1.2 Scope of ICZN and criteria of name availability

I.6.3.1.3 Name-bearing types

I.6.3.1.4 Principle of priority and principle of coordination

I.6.3.1.5 Synonymy

I.6.3.1.6 Homonymy

I.6.3.1.7 Universal rules and powers of the Commission

I.6.3.1.8 Spelling

I.6.3.2 Rank-based names of higher taxa

I.6.4 Basal format of typified names and hierarchy-based (hierarchical) nomenclature

I.6.4.1. Basionym of species name

I.6.4.2. Basal format of typified names

I.6.4.3. Hierarchical names

I.6.4.4. Priority of genus- and family-group names

I.6.5 Circumscription-based (circumscriptional) nomenclature

I.6.5.1 Circumscription-related terms

I.6.5.2 Criteria of availability for circumscription-based names

I.6.5.3 Circumscription fit

I.6.5.4 Validity of circumscription-based names

I.6.6 Name-related misconceptions

I.6.6.1 Customary interpretation of non-typified names

I.6.6.2 Example of myth-creating: theory about polyphyly of Hexapoda

I.6.7 Combining circumscription-based and hierarchy-based nomenclature

I.6.7.1 Usage of different nomenclatures

I.6.7.2 Format of species name in non-rank-based nomenclature

I.6.7.3 Sliding binomina and polynomina

I.7.1 Catalogues of names

I.7.2 Principles of zoological catalogues

I.6. Principles of nomenclature of zoological taxa

Why do we need rules of nomenclature? The number of species and supraspecific taxa of animals with which researchers have to deal is measured in the millions; it is so great, that causes serious difficulties with nomenclature. No human language has a vocabulary to name all known taxa, and no one can master such number of names. Other fields of knowledge also deal with large numbers of objects far exceeding the capability of everyday language. These are, for example, great numbers of celestial bodies, geographic objects, endless number of chemical substances and others. However, in geography, we can unambiguously pinpoint any object – no matter how many times it has been renamed (as is often the case) – by referring to the object's coordinates. In chemistry we can refer to a substance by writing down its unique structural formula.

In contrast to many other objects, living species cannot be given such ultimate definitions. Species differ one from another in indefinitely large number of characters that can be described in any number of ways, so comparing descriptions we can never be sure whether the species they refer to are identical or not. Each species has infinitely large number of characters that can be used as identifiers; no description or illustration could reflect them all (here should be noted that picture without description never can be enough, because a picture can only show a single or a few specimens, while what we need is understanding the features of a species as a whole). Because of this, descriptions report only each species' differences from already known ones. As a result of this, when a previously unknown species is discovered those older descriptions turn to be insufficient, because they do not provide comparison with this newly discovered species. Thus the need arises to refine and elaborate the descriptions of formerly described species in order to accommodate additional forms.

For example, in XVIII–XIX centuries lepidopterists used to believe it was enough to describe in detail the wing patterns accompanying the description by an accurate colour illustration. Later it was found that some butterfly species have identical complex wings patterns, but are easily distinguishable in genital structure, whose examination requires treating butterfly abdomens in alkaline solution; other butterfly species can be reliably identified only by chromosome number and/or shape. The old descriptions lack those essential details, so updated descriptions of species known for a long time had to be drafted. In the future we will likely face the need to supplement such descriptions with even more morphological, anatomical, biochemical or molecular-level details.

When species description is changed, we cannot be sure that the author of the new description does not confuse the species and does not describe another species under the same name. Since neither original description nor amended ones can be entirely reliable, we need strict and coherent rules of naming organisms to help us untangling intricate cases.

The easiest way to come to an agreement on which names for which taxa should be used, is to have an official list of correct names published by a competent international body. However, such a solution is only possible if the set of taxa we need to name would be known and constant. However, every year dozens of thousands of previously unknown species are being described, dozens of thousands of already described species get redefined, thousands of new genera and subgenera and many new families are established, and new classifications suggested with new meanings assigned to old specific, generic, family and other names. No panel could issue competent decisions on the usage of every single name under such overwhelming pressure.

Even when all animals will be described at least formally (that is impossible in foreseeable future) the number of zoological taxa would not stabilize. As shown above, the classification of animals is non-stable (see I.5.3.3) and this instability is inevitable, because we are to come to a natural, phylogeny-based classification – the only one that makes sense – while we can only move closer reconstructing animal phylogeny bit by bit, using for this purpose all biolgical knowledge receiving from various researches.

Because of this, to regulate the usage of taxonomic names we need universal rules of nomenclature, which would give any worker answers about what to do with this or that name without submitting every case to a commission.

The most elaborate rules include the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN, or ICZN Code), International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants, International Code of Nomenclature of Procaryots, and some other codes which govern rank-based names of species and other biological taxa (about the concept of rank-based name see I.6.2 and I.6.3 below). These codes are enacted by competent international bodies and are binding for all biologists. The codes (ICZN being the one relevant to zoologists) provide universal rules based on which anybody can decide how any particular name should be dealt with. Only in rare cases where these rules fail to help with a name-related issue, the Commission makes its special ruling. So regulating names by official lists also occurs, but this involves just a small fraction of names.

Some categories of names of taxa (see I.6.2 and I.6.5) are not regulated by codes in effect. their use is regulated by spontaneously emerging traditions, which by now has become insufficient. In this book we formulate universal rules of using such names. Unlike the provisions of ICZN (see I.6.3.1) and other international codes, the rules suggested here for rank-based names of higher taxa (I.6.3.2), hierarchy-based names (I.6.4) and circumscription-based names (I.6.5) are not official and thus not mandatory. Some principles apply to all rules herein discussed, including concepts of availability, validity and priority (I.6.1).

Non-interference of the rules of nomenclature to taxonomy. It is crucial not to confuse issues of nomenclature with those of taxonomy (since it is crucial not to confuse a name with with an object to which it belongs). Taxonomy is a science and hence can not be subject to outside dictate: researcher will decide which principles of taxonomy should be applied and what kind of classification created; he may choose to base his classification on phylogeny or something else, he may adopt or reject any phylogenetic hypotheses and follow any way of designing a classification – cladistic, numerical, gradistic, or any other. Since Renaissance times the science runs on the principle that no authority and no elected body can impose opinions on a scientist, the only thing capable to change his mind being logical argument. In contrast to taxonomy, nomenclature is not a science, because the names are artificially produced. So a nomenclature can be subject to rules adopted by a competent body and binding for every worker in the field; such rules are indeed provided by applicable international codes. Each of these codes proclaims the non-interference of nomenclatural rules to taxonomy. As the preamble of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature says, «The objects of the Code are to promote stability and universality in the scientific names of animals and to ensure that the name of each taxon is unique and distinct. All its provisions and recommendations are subservient to those ends and none restricts the freedom of taxonomic thought or actions».

I.6.1.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF NOMENCLATURE

OF BIOLOGICAL TAXA

In the paragraphs I.6.3–I.6.5 below various principles of nomenclature of taxa will be discussed – both officially set forth in the last version of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, and unofficial, offered to a reader's discretion. But first we need to take a look at the concepts shared by all types of nomenclature – these are concepts of availability and validity, and the principle of priority (I.6.1.2).

I.6.1.1. Availability and validity of names

The taxonomic name which should be used is called valid (accepted, correct). The valid name is chosen, subject to the rules of nomenclature, among the names considered to be available for purposes of the same code. Thus, an available name can be valid or not, while an unavailable name is never valid. Availability criteria vary depending on nomenclature (see below). The following points are shared by all codes:

Availability of a name is established by a set of availability criteria. These include: the name must be published after a certain date designated as starting date for this nomenclature (January 1st, 1758 for the names regulated by ICZN and other zoological names; botany and bacteriology use other dates); the name must have certain format (particularly, all taxonomic names should be Latin or latinized); the text of the name's first publication must meet certain requirements (they vary depending on code and name category). Only names meeting all availability criteria are considered available for purposes of a given nomenclature, so within a nomenclature many different available names can be created for a taxon, while available names for different taxa may be identical.

Different available names given to the same taxon are termed synonyms (synonyma). The concept of synonymy applies only to names subject to the same nomenclature, because the names unavailable under that nomenclature are not considered synonyms. Objective synonyms (synonyma objectiva) are different names deliberately given to the same taxon; they may appear, for example, when a new name is published to replace the existing one (about objective rank-based synonyms – see also I.6.3.1.5). Subjective synonyms (synonyma subjectiva) are different names of such taxa which are differently defined but are identical from a worker's point of view. The concept of subjective synonymy is fundamentally different in rank-based and circumscription-based nomenclatures (see I.6.3.1.5 and I.6.5.3), while in hierarchy-based nomenclatures it doesn't exist.

Identical available names given to different taxa are termed homonyms. Junior homonyms are also referred to as preoccupied names. Just like synonymy, homonymy may only exist within the scope of the same nomenclature, because names unavailable under this nomenclature are not considered homonyms. If two different taxa have identical names belonging to different nomenclatures (i.e. only one of these names is available under each code), such names are termed hemihomonyms (hemihomonyma) (Starobogatov 1991).

To assign every taxon one single name and make each name refer to a single taxon (i.e. to get rid of synonyms and homonyms), a single valid name is to be chosen among all available names of each taxon and among all identical names suggested for different taxa. Such choice is made based on the rules of the same nomenclature whose rules are used to establish name availability. So, within the scope of one nomenclature we come to situation where every taxon has a single valid name and each valid name refers to a single taxon. At the same time one taxon may have several different names considered valid under different nomenclatures, while different taxa can have identical valid names under different nomenclatures (i.e. hemihomonyms may coexist).

I.6.1.2. Principle of priority

Different codes provide different ways to choose a single valid name among available names, but some sort of priority principle always applies. According to this principle, the valid name is the one which was the first, among all competing available names, to meet the availability criteria – i.e. the one published in compliance with all applicable requirements. Priority must be subject to some restrictions: it applies only to names published after a certain date (1st of January 1758 in zoology); all names published prior to this date are considered unavailable (see 1.6.1.1). Without such restriction no name could be deemed valid with any certainty, because the time before its first publication would be indefinitely long and it would be impossible to make sure that there is no earlier published name (which would be of higher priority).

The principle of priority implies that every name must have its authorship, because priority does not apply to anonymously published names. Authorship means not just the author's name, but his particular paper with the exact date of publication.

Aim of the priority principle is to prevent arbitrary renaming of taxa. Anyone can make up a new name for any known taxon and publish such name meeting all availability criteria, but priority principle precludes such names from becoming valid, because the only name of this taxon that may be valid is its oldest available name. Thus, priority principle discourages redundant name creation and allows zoologists to reach consensus on which one of the existent names should be used. In contrast to any other criteria for choice of a single valid name name among several available ones, the priority criterion excludes disagreements and gives a univocal result: if two names had been published with at least one day in between, there can be no doubt which one is older; among names published in the same paper, the one which appears first takes priority.

The principle of priority has an important shortcoming: the valid name (i.e. the name which should be used) is the earliest one, which is usually also the most problematic in terms of which species does it refer to. When an author describes a new species, he only points out what distinguishes this species from those previously described. Unaware of the forms yet to be discovered, he is in no position to indicate all characters necessary to distinguish it from the forms not described by then. So, generally, the later a species is described, the more comprehensive its original description is (setting aside occasional substandard and inaccurate descriptions). To redefine previously described species the expert must reexamine specimens on which the species's original description was based; the earlier it was described the higher are the odds that these specimens can be lost or damaged.

In cases where rigorous enforcement of priority principle may result in much inconvenience or is unfeasible, special ruling is to be made to override priority. For names subject to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (see below), such rulings on selected names are issued by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.

Various nomenclatures vary in how priority principle is applied and in defining sets of names among which the oldest one should be chosen. For example, in rank-based nomenclatures (see below) the oldest name is chosen only among names assigned to taxa of the same rank or rank group; particularly, the name of a botanical genus should be the oldest among generic names, while the name of a zoological genus is selected from a combined pool of generic and subgeneric names. So the result of name choice using priority principle will depend upon applicable rules.

An alternative to the priority principle is the principle of the first reviser, i.e. the first author who believes some names to be synonymous has the right to choose valid names among available ones. On limited use of this principle in ICZN. Since the establishment of subjective synonymy is not a nomenclature act, and the authorship of the first establishment of synonymy is usually not indicated, the right of the first reviser does not contribute to the stability of the nomenclature.

I.6.2. Different types of nomenclatures and names

Why do different types of nomenclature coexist? As shown above(I.5.3.2), classification cannot be permanent; instead, it is subject to incessant change, because it relies on phylogeny, and there is no direct way to have phylogeny revealed; since all methods of reconstructing phylogeny are indirect and rely on the entire body of biological knowledge, and the latter is continuously growing, the process of adjusting our idea of phylogeny, and hence changing classification, will be endless as well. So there is no hope that a perfect and final classification of living organisms would ever be built. Should a constant classification appear, rules of nomenclature would become redundant, as the names of all taxa in such classification will only need to be validated once and for all. It is the inability to create such classification that forces us to set universal rules of naming taxa.

Aim of any principles of nomenclature is to stick univocally names to taxa. However, any taxon has many different attributes. The attributes of taxa are circumscription (hereinafter, the circumscription of a supraspecific taxon means a concrete set of species included in this taxon), diagnosis, rank, position in the classification, etc. It is impossible to stick a name with all such attributes at once, because any change of the classification entails changes in combination of its attributes. For example, in different classifications taxa of the same circumscription may have different ranks, different diagnoses or be assigned to different higher taxa; and vice versa, taxa of the same rank can have different circumscriptions, and so on. Nomenclature of taxa must support ever-changing classification, which implies that a name can only be associated with just one attribute of a taxon.

Based on the attribute with which a name is associated, several fundamentally different types of nomenclatures can be recognized, viz. rank-based, circumscription-based, description-based, phylogeny-based, hierarchy-based, etc. In following paragraphs we will explain why only rank-based, hierarchy-based, and circumscription-based ones are meaningful.

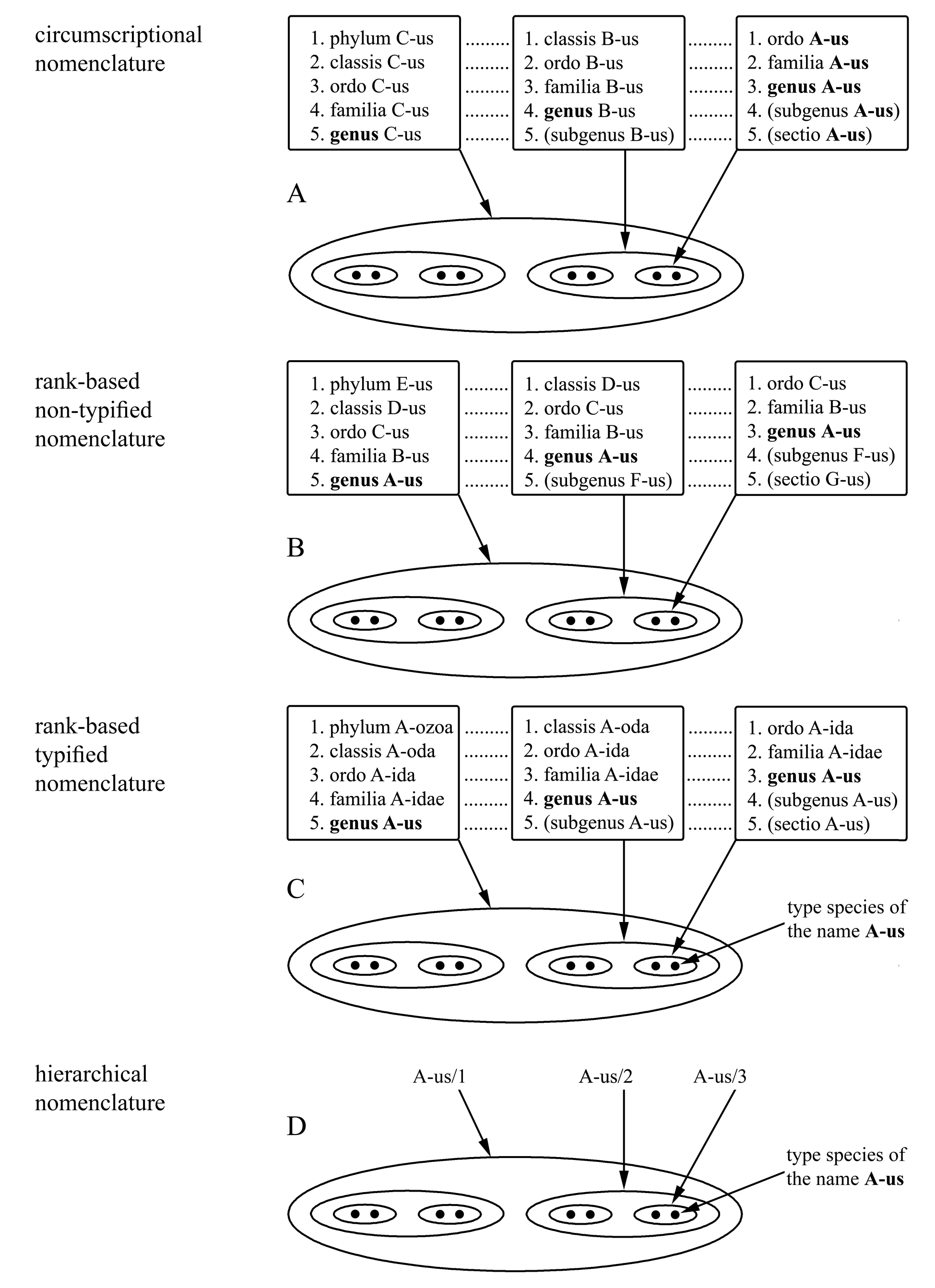

Rank-based (ranking) nomenclatures. In these nomenclatures a name is associated with a certain rank of taxon and is subject to change whenever the rank changes, but remains the same when other attributes (such as circumscription or position) change (Fig. 1.8). The ranking nomenclature still plays a major role in taxonomy, because all international codes, including ICZN, are based on this principle. However, the ranking nomenclature has significant shortcomings (I.6.6) and is not used in this book. For details about ranking nomenclatures see I.6.3 below.

Circumscription-based (circumscriptional) nomenclatures. Under this approach a name is associated with a certain circumscription of a taxon without regard of its rank or position (Fig. 1.8). This principle of nomenclature is traditionally applied to higher taxa, but coherent rules of circumscriptional nomenclature were not formulated until recently. For details see I.6.5 and I.6.7 below.

Description-based nomenclatures. In this type of nomenclature a name is associated with the definition (diagnosis) of a taxon and changes accordingly whenever the taxon is redefined. Some authors tried to use this principle.

For example, different authors referred to the same taxon, springtails, the names Collembola (derived from collophor or embolium, the sticky ventral tube), Podura (after the abdominal fork), Oligomerentoma (reflecting reduced number of abdominal segments), Protomorpha (from protomorphosis – a peculiar mode of embryogenesis), and others.

Following this path we can change names of taxa over and over, but none will fully reflect the diagnosis. That's why descriptive nomenclature is never stable and there is no point using it. In his early works, C. Linnaeus proposed a nomenclature in which the name of a species included from 2 to 13 words and was at the same time a diagnosis of this species; later he elaborated a binary nomenclature in which the name of a species always consists of two words and may not correspond to either the diagnosis or part of the diagnosis of that species (Linnaeus 1758); it is this binary nomenclature that has become universally recognized.

Phylogeny-based (phylogenetic) nomenclatures. Recently some authors suggested a phylogenetic (cladistic) nomenclature, where the name is associated with a common ancestor of the taxon, which means a name may only refer to a holophyletic taxon evolved from such ancestral species.

With such a choice of the attribute of the taxon, the very existence of the name turns out to be a statement about holophily of

this taxon; therefore, the use of phylogenetic nomenclature is dangerous in that it can lead to the substitution of evidence for holophilia of a taxon by referring to the presence of a phylogenetic name for this taxon.

Fortunately, the rules of phylogenetic nomenclature proposed so far are not applicable, as they lack criteria for the applicability of names that would make it possible to determine which names fall under the rules of phylogenetic nomenclature and which do not.

The authors who make up the rules of phylogenetic nomenclature consider the indication that the new name refers to a holophyletic taxon as such a criterion; however, the new name of a holophyletic taxon in any other nomenclature is accompanied by the same direct or indirect indication.

In the form in which phylogenetic nomenclature is proposed by some authors (having an extremely vague idea of the principles of nomenclature, and therefore not cited here), this nomenclature directly contradicts the existing International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

(ICZN): for example, family names formed according to the rules of the ICZN rank-based nomenclature (see below, I.6.3.1) are proposed to be used according to completely different rules of phylogenetic nomenclature.

Such use of the same name in different nomenclatures contradicting each other is completely unacceptable, since it only leads to nomenclature chaos.

Hierarchy-based (hierarchical) nomenclatures. In this book we use circumscription-based nomenclature and a hierarchy-based nomenclature developed by the author. In hierarchy-based nomenclature a name is associated with the taxon's placement within hierarchical classification and does not depend on rank (Fig. 1.8). This system is based on recently enacted International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, yet overcomes some important flaws of the ICZN's ranking principle. For details see I.6.4 and I.6.7 below.

Fig. 1.8. Principal difference between circumscription-based, rank-based and hierarchy-based nomenclatures. A – circumscriptional nomenclature (non-typified); B – rank-based non-typified nomenclature; C – rank-based typified nomenclature; D – hierarchical nomenclature (typified). Black rings indicate species, ellipses – supraspecies taxa. In all figures A–C, names for each taxon are given according top five various arrangements of ranks indicated by numbers from 1 to 5. Everywhere instead of Latin taxa names, arbitrary A-us, B-us at al. are given. One of the ranks – genus – and one of the names – A-us – is everywhere marked by bold font.

Depending on usage mode, names may be rank-based, circumscription-based, hierarchy-based, etc., while by format they can be typified or non-typified, unified or non-unified.

Typified and non-typified names. Typified name (nomen typus-fundatum) is derived from the name of type genus (about type genus see I.6.3.1). Many rank-based names of suprageneric taxa and all hierarchy-based names are typified. Non-typified are rank-based names of species-group and genus-group, and supraspecific circumscription-based names. Besides tis, some non-typified names are used as rank-based, that is ãòâóûøêôèäó (see I.6.6.1).

Unified and non-unified names. Unified (or standardized) names (nomina unificata) are such rank-based names whose endings are identical in all taxa of the same rank but differ in names of different ranks.

Table I.5 summarizes name format types.

Table I.5. Examples of typified, non-typified, unified and non-unified names: each contains names of two superorders – containing damselflie and dragonflies (with senior generic name Libellula) and containing stoneflies (with senior generic name Perla).

|

typified: |

non-typified: | |

|

unified: |

Libelluloidea Perloidea |

Odonatoidea Plecopteroidea |

|

non-unified: |

Libelluloidea Perlariae |

Odonata Plecoptera |

I.6.3. RANK-BASED (RANKING) NOMENCLATURES

Rank-based nomenclatures are those where a name is strictly associated with rank but remains unaffected by the circumscription or position of the taxon (Fig. 1.8). Significant shortcoming of the ranking principle of nomenclature is that names are associated with a purely conventional taxon's attribute, i.e. its rank (see I.5.4.2 above). In different classifications the same rank-based name can be assigned to taxa of different circumscription while taxa consisting of the same members (i.e. having identical circumscriptions) should be given different names within the same rank-based nomenclature if such taxa have different ranks. As a result, usage of the rank-based nomenclature often causes confusion (see I.6.6 below).

An advantage of the rank-based principle of nomenclature is that it allows to create strict rules and thus assure a unique valid name for every taxon in any given classification. Until recently all such rules were invariably rank-based, so in spite of its obvious shortcomings this approach is generally recognized and widely used. (See, however, I.6.4 and I.6.5 below to learn about newly developed coherent rules based on non-ranking principles).

Ranking principle is used in all currently effective nomenclatural codes (ICZN, International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants, International Code of Nomenclature of Procaryots). ICZN governs names of taxa ranging from species to superfamily. Besides this, ranking are some names of higher zoological taxa (i.e. taxa with ranks higher than superfamily) not regulated by ICZN (see I.6.3.2 below).

I.6.3.1. Names regulated by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN)

I.6.3.1.1. Historical. First attempts to establish rules of nomenclature date back to the end of XVIII century. In 1842 Strickland's «Rules for Zoological Nomenclature» were published, in 1877 – the Dall's code, in 1905 – «Regles Internationales de la Nomenclature Zoologique». The first edition of the «International Code of Zoological Nomenclature» was published in 1961, the second (somewhat revised) in 1964, the third (amended) in 1985; currently the forth (amended) edition is in force, published in English and French in 1999.

The current Code contains 90 articles governing the status of names and a number of recommendations for authors and editors of scientific publications, whose adherence is necessary to promote stability of zoological nomenclature.

I.6.3.1.2. Scope of ICZN and criteria of name availability. ICZN regulates usage of names applied to zoological taxa of the species group (which includes species and subspecies), the genus group (which includes genera and subgenera), and the family group (including superfamilies, families, subfamilies, tribes, etc.), but does not apply to taxa lower than subspecies or higher than superfamily. Zoological taxa are taxa consisting of organisms currently considered to be animals (since nomenclatural rules may not affect scientific freedom, they say nothing about which organisms should be considered animals).

Availability criteria somewhat vary depending on group (species-group, genus-group, and family-group) and in different cases (the concept of availability is discussed in more details in I.6.1.1 above); here we will only discuss some of these criteria.

The starting point of zoological nomenclature is January 1, 1758, considered to be publication date of the 10th edition of «Systema Naturae» (Linnaeus 1758). The reason why the tenth edition has been chosen is that in that edition Linnaeus for the first time used binary nomenclature in a consistent fashion. All names published before 1758 are automatically considered to be unavailable (including names used by Linnaeus himself in the previous editions of «Systema Naturae»). Accordingly, all names used in 10th edition of «Systema Naturae» are considered published for the first time in 1758, and Linnaeus is regarded as their author (though many of these names had been in use well before Linnaeus).

To become available, the name has to be Latin or latinized, i.e. written in Latin letters only and treated in accordance with the rules of Latin grammar. Words of any derivation (Latin, Greek, or other languages) or any combinations of letters may be used as zoological names.

A name becomes available only after its publication in scientific literature; unpublished names are unavailable. So the author publishing a scientific name has to be fully aware whether this name has already been used or is a new one. For a name already used, one should make sure that it is available (in such case publishing this name will not affect the nomenclature). In case the intent is to publish a new name, the author must analyze everything in the Code applicable to that case and meet all availability criteria to make sure the suggested name will become available. If by some reason it is impossible to publish a name of a new taxon in compliance with all the provisions of the Code, it is better to use some expressly unavailable designation (such as number) instead of Latin name, to show that no claim of availability is being made. In any case, suggested names should be made either unambiguously available or expressly unavailable in terms of ICZN, because names of dubious availability destroy nomenclatural stability.

Species-group name, i.e. the one of a species or subspecies (sometimes, mainly in botany, called epithet) becomes available only if originally published as a part of a binomen, i.e. in combination with a generic name (this combination is termed the original combination). If systematic position of the species changes, the same epithet may appear in combination with another generic name, but with this its availability does not disappear, and its authorship and date are not changed. We may change generic name in a binomen, but may not use the epithet without a generic name. This restriction is due to the fact that many epithets are repeatedly used in zoological nomenclature, and homonymy rules in species-group (see I.6.3.1.6) apply only to epithets associated with some generic name.

I.6.3.1.3. Principle of fixatoion of nomenclatural types. The most important principle of rank-based nomenclature is the principle of fixation of type-taxa, or name-bearing types. For each taxonomic name a type is designated (type taxon); the type taxon is one of subordinate taxa within the taxon to which the name applies.

For a name of species group (species or subspecies) the type is a specimen – one of specimens of this species preserved in collection. The type specimen is chosen arbitrarily, but once such specimen is designated, it cannot be changed. That's why type specimens are being marked with special labels and preserved with extreme care; even if damaged, destroyed, or lost, a type can not be replaced with another specimen. A single specimen designated as a type in the original description is termed holotype (holotypus); if the type series includes other specimens, they are termed paratypes (paratypi). If the original description was based on several specimens, but no holotype has been designated, all the specimens are termed syntypes (syntypi); subsequently, one of them can be designated (by the same or another author) as a lectotype (lectotypus), in which case all the rest of syntypes become paralectotypes (paralectotypi). If the type series is lost, a neotype (neotypus) may be designated to solve nomenclatural issues that require a type specimen. The holotype, lectotype, or neotype is the actual type of a specific name.

The type of a genus-group name (generic or subgeneric) is a type species; in some older publications type of generic name was termed «genotype», but recently this word is used as a genetic term only. The type species of a generic name should be designated in the original description of the genus, or – for older names (where this had not be done originally) – in a later publication. In this case the type species designated the first is considered to be valid.

Each name of the family-group taxon (superfamily, family, subfamily, tribe, subtribe, etc.) has its type genus and is derived from the latter's name by change of ending.

The types are often referred to as types of species, genera, families, etc., but in fact are types of the names, not the taxa. A name may have no more than one type, but a taxon includes as many types as many available names it has.

At the same time, the type itself is always either a specimen or a taxon (species or genus), i.e. a material object, not a name. Thus, if a species gets its name changed, this species (with a newly assigned name) remains the type of the same generic name as before.

The types serve to prevent transferring names from one taxon to another. If a taxon's circumscription changes, the former name applies to the taxon which includes the type of this name. For example, when a group once regarded as a single genus is divided into smaller genera, the genus which includes the type species of the former generic name keeps that name.

For example, Linnaeus in his classification included all mayflies in a single genus and gave it the generic name Ephemera Linnaeus 1758 (the date ascribed based on ICZN rules of priority, although the name Ephemera had been in use far before). Since Linnaeus did not designate a type species, Latreille (1810) designated Ephemera vulgata Linnaeus 1758 as the type species for this generic name. So ever since, as classification changed, the name Ephemera could only be applied to such genus including the species E. vulgata, while no genus which didn't include this species could be named Ephemera. In different periods various workers applied the name Ephemera to mayfly taxa of different content, but in every classification Ephemera was the only taxon which both had the rank of genus and included the species E. vulgata.

In the same way a type specimen is used to deal with a species-group name. If, for example, it is discovered that the same specific name is being applied to more than one species, the original name should be applied to animals conspecific with the type specimen. Sometimes an original description establishing a species's name mentions only characters shared by several species; in this case the type specimen should be reexamined to decide which of these species will bear the name.

Types in nomenclature are served to decide which taxon should bear this or that name, but not to decide which species does this or that specimen belong to, or which higher taxon should include this or that species, i.e. to resolve issues of nomenclature, not taxonomy. So, designating name-bearing types (that is a mandatory procedure in modern biology) basically differs from the typological approach in taxonomy (hardly used today by anybody, because no arbitrarily selected type can provide a basis for natural classification).

I.6.3.1.4. Principle of priority and principle of coordination in zoological nomenclature. All names subject to ICZN are divided into three droups. (1) Names of the species group, to which belong names of species and subspecies; such name is a second name in binomene (while the first name is a name of the genus), is always written with a small letter and represents an adjective or singular noun in the nominative or genitive case. (2) Names of the genus-group, where belong names of genera and subgenera; such name is always written with capital letter and represents a singular noun in the nominative case. (3) Names of the family group, where belong names of all suprageneric taxa up to superfamily, i.e. superfamilies, families, subfamilies, tribes, subtribes, etc.; such a name is formed from the name of the type genus by replacing its grammatical ending and suffix with an ending corresponding to the rank (-oidea for a superfamily, -idae for a family, -inae for a subfamily, -ini for a tribe, etc.); such a name is a plural noun in the nominative case. ICZN rules for each group are different. According to the ICZN, each of these three groups has own coordination. The principle of coordination works as follows:

Within the species-group (i.e. among species and subspecies names) a name available as a name of species is automatically available, with its authorship and date, as a subspecies name, and vice versa, available subspecies name is available, with its authorship and date, as a species name.

Within the genus-group (i.e. among the names of genera and subgenera) coordination works in the same way: a name of genus is automatically available as a subgeneric one, and vice versa; in both cases names keep their original authorship and date. Thus, the oldest (valid) name of a genus or subgenus is chosen among both generic and subgeneric names, not only among names of the same rank. In other words, availability, authorship, and date of publication are effective throughout the genus-group, not just among the names of the same rank.

For example, the name Heptagenia Walsh 1863 was originally established for a genus; subsequently the genus Heptagenia (by that time its circumscription has changed, as it happens quite often in ranking nomenclature) was divided into subgenera. One of these subgenera invariantly includes H. flavescens, the type species of the generic name Heptagenia. The correct name of a subgenus should be such available genus-group name (whether generic or subgeneric) which is the oldest among names whose type species are members of this subgenus. Undoubtedly, in this case such name is Heptagenia because it is the oldest one among all names whose type species are members of the entire genus, not just the subgenus. Thus, the subgenus containing H. flavescens should be named subgenus Heptagenia Walsh 1863 in spite of the fact that Walsh established no subgenera in 1863.

So the principle of priority, as applied to the genus-group, works in such a way that whenever a genus gets divided into subgenera one of the subgenera is always assigned the same name as the genus where it belongs; such subgenus is termed the nominotypical subgenus.

In the family group, according to the current ICZN, works a separate principle of coordination, which is independent from the coordination in the genus-group. Family-group names are typified (see I.6.2), each being derived from a genus-group name by replacing its ending with a standardized suffix and ending corresponding to rank; so, in contrast to names of different ranks in the genus-group (i.e. generic and subgeneric names), the names of different ranks in the family-group differ by their endings. Coordination in the family-group means that authorship and date of any name in the family-group (superfamily, family, tribe, subtribe or any other) automatically applies to all family-group names derived from the same generic name. Hence, the oldest (valid) name for a family-group taxon should be chosen not only among the names of taxa having the same rank, but among all family-group names whose type genera are members of that taxon. When the standardized suffix and ending are changed, the authorship and date are not changed. In other words, a valid name of a family, subfamily, or another family-group taxon is derived from such generic name from which the first family-group name had been derived. Coordination within the family group is independent from coordination within the genus group; this means the genus-group name from which the family-group name is derived is not necessarily the oldest one.

For example, genera Heptagenia Walsh 1863, Ecdyonurus Eaton 1868, and others are considered members of the same family. To obtain the name for this family, we must chose one of these genera and change its ending to «-idae». The fact that the oldest generic name is Heptagenia is irrelevant, because the priority within the genus-group does not affect the priority within the family-group. The first family name had been derived from the name Ecdyonurus – Ecdyonuridae Ulmer 1920. However, there is an even earlier subfamily name Heptageniinae Needham 1901 derived from the name Heptagenia. According to the principle of coordination, the correct family name with appropriate authorship will be Heptageniidae Needham 1901 (despite the fact that in 1901 Needham neither considered this taxon a family nor used the ending -idae). Superfamily Heptagenioidea, tribe Heptageniini, and any other family-group name derived from the generic name Heptagenia will keep the same authorship. In application to the family-group, the principle of coordination means that within this group the name of one of directly subordinated taxa will always be derived from the same generic name as the name of the next higher taxon. For example, the superfamily Heptagenioidea Needham 1901 includes the family Heptageniidae Needham 1901 with the subfamily Heptageniinae Needham 1901; if any tribes are recognized, one of them is named Heptageniini Needham 1901.

But since there is no coordination between the genus group and the family group, the type genus does not necessarily retains validity of the name from which the family name was derived.

For example, there is a valid family name Polymitarcyidae, yet no valid generic name Polymitarcys, from which it had been derived. Within the family-group, the name Polymitarcyini Banks 1900 (derived from Polymitarcys and originally given to a tribe) is older than the name Ephoronidae Traver 1935 (derived from Ephoron and originally assigned to a family), while within the genus-group the name Ephoron Williamson 1802 is older than Polymitarcys Eaton 1868, considered to refer to the same genus.

The rule about independent coordination within the family group was introduced in 1961. Till then, only species-group and genus-group names were subject to coordination rules, so different authors applied different principles to choose type genera for family-group names. That's why so many family-group names still circulate defying current rules.

Under the current Code, the principle of priority strictly applies only to cases where a valid name is being chosen among names published on different dates; competing names published in the same paper are subject to another principle – the principle of the first reviser (see I.6.1.2). The first reviser is the first worker to establish synonymy and to choose the valid name among competing ones.

I.6.3.1.5. Synonymy. Like in any other typified rank-based nomenclature, in the nomenclature of ICZN different names referring to the same taxon are regarded to be objective synonyms if they have equal ranks and the same type (i.e. type specimen or type taxon – see I.6.3.1.3); different names referring to the same taxon are regarded to be subjective synonyms, if they have equal ranks, but different types.

For example, in the classification where the genera Heptagenia, Ecdyonurus, Rhithrogena, Epeorus and Arthroplea are all members of the same family, the family name will have the following synonyms:

Heptageniidae Needham 1901

= Ecdyonuridae Ulmer 1920

= Arthropleidae Balthasar 1937

Taxa circumscriptions have no effect here: e.g., the name Arthropleidae has never been applied to a family containing all these genera, being established for a small family including only the genus Arthroplea.

As we can see, the names considered synonyms under ICZN may belong to taxa of quite different circumscriptions. So the rank-based synonymy is quite different from circumscription based one (see I.6.5.3), and these concepts should be clearly distinguished.

According to the principle of priority, only the oldest, senior synonym may be the valid name of a taxon. All other, junior synonyms are invalid and thus not used, but are kept in the nomenclature (i.e. remain available): they are considered for purposes of establishing homonymy (see below) and may also become valid names as classification changes.

I.6.3.1.6. Homonymy. Homonyms are identical names given to different taxa. The ICZN requires homonyms to be eliminated; here, as with synonyms, the principle of priority also applies.

In zoological nomenclature species-group name (independently, specific or subspecific) may not be repeated within a genus, i.e. combined with the same generic name. If a subgeneric name is used, it does not affect the homonymy of the species-group names. Homonymy in the species group may be primary (when original combinations of different species have the same generic name with identical epithets) and secondary (when original combinations of different species had different generic names with identical epithets but after being reclassified such species appeared in the same genus). According to ICZN, renaming junior secondary homonyms is reversible but renaming junior primary homonyms is irreversible.

Genus-group name (generic or subgeneric) should not repeated within the animal kingdom (i.e. within zoological nomenclature). In this respect zoological, botanical, and bacteriological nomenclatures are independent, i.e. each of these nomenclatures disregard the names used in the others. This means, for example, that the same word can be the name of both an animal genus and a plant genus, but cannot be applied to more than one animal genus.

I.6.3.1.7. Universal rules and powers of the Commission. Nomenclatural rules are designed to promote name stability, that's why they tend to perpetuate practice already in place. However, no single code, however carefully phrased, may reflect established custom for every individual case.

For example, while it is generally accepted that the valid name is always the oldest one among available names of a taxon, in some cases a well-known taxon may have generally accepted and long used name other than its oldest available name. Under ICZN rules, this widely circulated name is to be replaced with the technically correct one, but since in this case revitalizing a name hardly familiar to anybody would compromise nomenclatural stability, the International Commission for Zoological Nomenclature issues a special ruling to formally establish such generally accepted name as the correct one by suppressing the older unused name or otherwise declaring it unavailable.

Depending upon situation, the Commission may suppress a name either for purposes of priority but not for purposes of homonymy (so that such name becomes invalid but another identical name may not be created) or for purposes of both priority and homonymy. The Commission may validate designation of a type taxon, which contradicts the general rules of the Code. In all cases, rulings of the Commission on certain names has priority upon rules of the Code.

I.6.3.1.8. Spelling. The Code regulates not only choice of names, but also their spelling. As we have already mentioned, the names should be Latin or latinized (i.e. spelled using Latin letters and treated in accordance with the rules of Latin grammar); in terms of etymology, any derivation is allowed (Latin, Greek, other languages, or arbitrary combination of letters).

All genus- and family-group names begin with a capital letter, while species-group names are always lowercase. In old papers some species names (such as those derived from personal names) used to be capitalized; now they should be spelled in lowercase only. Diacritic marks, apostrophe and diaereses, used in some names, should be omitted in zoological publications (e.g., the name originally spelled Baёtis is now Baetis). Hyphens, punctuation marks, or digits in compound names are also excluded from modern zoological nomenclature, and each name is spelled as a single word (e.g., decempunctata instead of 10-punctata, sanctijohannis instead of s-johannis or st. johannis), with the only exception of names including a Latin letter used to denote descriptively a character of the taxon (such names are spelled with a hyphen, e.g., c-album).

Species names is binary, i.e. consists of a generic name followed by a species name written separately without punctuation in between, e.g., Heptagenia sulphurea. The name of subspecies in zoology consists of three names: the proper subspecies name is written after the generic and species names, also without punctuation marks, e.g., Heptagenia sulphurea dalecarlica. If the genus contains subgenera, the subgeneric name may be inserted in parentheses between generic and specific names, e.g., Heptagenia (Heptagenia) sulphurea. Due to this, no other word may be inserted in parentheses between generic and specific names. If the second part (the specific name, or epithet) of a binomen is an adjective, it must grammatically agree with the generic name, so as the generic name changes, the ending of the species name must be also changed to reflect gender. With this, subgeneric name in parentheses does not affect the gender of species name.

Citation of authorship is optional, yet usually recommendable. Authorship and date refer to the last word of the name. The name of the author who has made the name available – usually with the publication year after it – follows the name with no punctuation marks in between. Year can be given after the author's name either also with no punctuation marks in between (as in this book), or separated from the authors name by comma (no other punctuation marks are allowed). Many publications give the names of the authors without the year; such a spelling is formally permissible, but meaningless. The tradition of indicating the author without a year goes back to the XVIII–XIX centuries, when there were no nomenclature rules, and each author used the names at his own discretion; in this case, the indication of the author's surname made it possible to determine the meaning of the name.

For example, Linnaeus used the name Tettigonia for grasshoppers, and Fabricius used the same name Tettigonia for cicadas. In order not to confuse these names, the name of the grasshoppers was written as "Tettigonia Linn.", and the name of the cicadas as "Tettigonia Fabr."; however, the year of publication was not indicated, because in all of Linnaeus's publications the name Tettigonia referred to grasshoppers, and in all of Fabricius's publications it referred to cicadas.

Now the situation is different: according to the current rules of nomenclature, the meaning of the name is determined not by the opinion of its author, but by the publication that ensured the availability of the name; the year of publication of this publication is of decisive importance, as provides name priority; therefore, giving the surname of the author of the name makes sense only in combination with the year.

If the generic name had changed since the first publication, the authorship is cited in parentheses, e.g., Heptagenia sulphurea (Muller 1776), but Ephemera sulphurea Müller 1776, because this species, originally described by Müller as a member of Ephemera, was subsequently transferred to the genus Heptagenia.

If the author cited after a name is not the one who made the name available (such as the author of a new combination or the one who reconsidered the circumscription of the taxon) such citation should be separated from the name in a way other than using parentheses or a comma.

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, Appendix B6 contains the following recommendation: «The scientific names of genus- or species-group taxa should be printed in type-face (font) different from that used in the text; such names are usually printed in italics, which should not be used for names of higher taxa.» Accordingly, in this book we italicize all rank-based names of genus- and species-group (no matter how we treat them), while the names of other taxa (rank-based family-group names, hierarchy-based or circumscription-based names) are formatted otherwise (regular, bold, italics bold), depending on context.

I.6.3.2. Rank-based names of higher taxa

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature regulates names of taxa ranked not higher than superfamily. There is no generally accepted rules of naming higher taxa (orders, classes, phyla, etc.).

Some authors advocate introducing a mandatory standardized typified nomenclature of higher taxa. They suggest all names of higher taxa to be derived in the same manner as family-group names, i.e. by modifying names of type genera with endings to reflect the rank. There is no consensus on what such higher rank endings should be (see Table I.6). A number of established practices exist as to the use of typified names of higher taxa, depending on animal group.

The issue of how the principle of coordination should be applied to typified names of higher taxa also causes disagreement: we can use no coordination at all (as in botany), i.e. disregard other ranks' names while selecting the oldest name for a taxon of given rank; or several independently coordinated groups (e.g., order-group, class-group, phylum-group) may be established in the same way as the ICZN's independent family- and genus-groups; or else, we can coordinate typified names of higher taxa with the family-group. Actual names will depend upon which one of these alternatives is adopted.

Hence, to adopt standardized typified rank-based names, zoologists must agree on two points: (1) in order to make names endings generally accepted among zoologists, they have to reach consensus on which ending each rank will have, and (2) in order to make name bases generally accepted it is necessary to chose one of the possible ways to apply the principle of coordination.

Table I.6. Unified endings for

typified names of zoological taxa

|

|

Suffixes and endings for typified names

of higher taxa suggested by different authors: |

||||

|

Ranks of zoological taxa: |

Poshe |

Stenzel |

Hubbs |

Rohdendorf |

Starobogatov |

|

regnum |

|

-ontes |

|||

|

subregnum |

|

-ionti |

|||

|

superdivisio |

|

-ozoi * |

|||

|

divisio |

|

-ozoides * |

|||

|

sudivisio |

|

-ozoidi* |

|||

|

supersuperphylum |

-acea |

|

|

||

|

superphylum |

-aceae |

-ozoidea |

-ozoacei * |

||

|

subsuperphylum |

-acei |

|

|

||

|

phylum |

-aria |

-ozoa |

-ozoes * |

||

|

supersubphylum |

-ariae |

|

|

||

|

subphylum |

-arii |

-ozoina |

-ozoines * |

||

|

infraphylum |

-ozoines |

-ozoae * |

|||

|

supersuperclassis |

-omorpha |

|

|

||

|

superclassis |

-omorphae |

-odea |

-idees |

||

|

subsuperclassis |

-omorphi |

|

|

||

|

classis |

-oidea |

-oda |

-iodes * |

||

|

subclassis |

-ona |

-iones * |

|||

|

infraclassis |

-ones |

-ioni * |

|||

|

legio |

|

-omorphae |

|||

|

sublegio |

|

-omorphinae |

|||

|

cohors |

-iformes |

-omorphi * |

|||

|

superordo |

-ica |

-oilei |

-idea |

-iformii * |

|

|

ordo |

-ida |

-oidei |

-ida |

-iformes * |

|

|

subordo |

-ina |

-oinei |

-ina |

-oidei * |

|

|

infraordo |

|

|

-omorpha |

-oinei * |

|

|

Ranks of family group taxa: |

Suffixes and endings according to

ICZN: |

||||

|

superfamilia |

-oidea |

||||

|

familia |

-idae |

||||

|

subfamilia |

-inae |

||||

|

tribus |

-ini |

||||

|

subtribus |

-ina |

||||

I.6.4. Basal format of typified names and HIERARCHY-BASED (HIERARCHICAL) NOMENCLATURE

A rank-free hierarchy-based typified nomenclature based on ICZN has been recently developed (Kluge 1998, 1999). Genus-group and family-group names, that are rank-based names themselves (see above), can be used not only in rank-based nomenclature but to derive hierarchy-based names as well, in which case type species of generic names (see I.6.3.1.3 above), authorship, priority and coordination all work just as provided by the ICZN (see I.6.3.1.4). In contrast to in the ICZN's nomenclature, in the hierarchy-based nomenclature no name is assigned absolute rank (such as genus, family, etc.), but refers rather to a relative rank, i.e. with the number of hierarchically subordinated taxa above it. That's why the hierarchy-based nomenclature can be used in rank-free classification. In cladoendesis the hierarchical nomenclature is used along with the circumscriptional nomenclature (see below, I.6.7).

Usage of the typified names in rank-free systematics is grounded on usage of the basal format of typified names (see I.6.4.2) and the basionyms of species names (see I.6.4.1).

I.6.4.1. Basionym of species name

According to the ICZN, a species name can exist only in the form of binomen, in which the first word is the name of the genus, and the second is actually the species name (species epithet) (see I.6.3.1.8). With this, the same word – the generic name – performs two completely different functions, each of which is quite complex in itself: on the one hand, the generic name indicates the systematic position of the species, on the other hand, it gives the name of the species a unique and distinguishes it from all other zoological species names (the number of which is measured in millions). The fact that the first word of the binomen should indicate the systematic position of the species makes the binomen extremely unstable: firstly, because the systematic position is the subject of scientific research and will never be finally determined (see I.4 and I.5), secondly, because in order to establish a generic name, it is necessary to determine which of the higher taxa has the genus rank, and the ranks are set arbitrarily (see I.5.4.2). Depending on the combination of the species epithet with one or another generic name, the epithet may or may not be the junior homonym of another name, and depending on this, it is renamed or restored (since the renaming of the secondary homonym is reversible – see I.6.3.1.6).

An invariable form of a species name is its primary binomen, or basionymum (termed protonymum by some ornithologists). This is the combination of species and generic names that was used in the publication, which provided the availability of this species name. If the basionyms of two different species coincide, then they are the primary homonyms, and the junior of them is renamed irreversibly (see I.6.3.1.6); due to this, basionyms are not repeated throughout the zoological nomenclature.

If the generic name of basionym does not correspond to the modern concept of the systematic position of this species, it should be written so that the reader does not mistake it for the name of the genus to which this species is now assigned. The rules of the ICZN do not recommend how to write such basionyms, so they are written in different ways. The most convenient way is to rearrange the species and generic names in places: first, a species epithet is written (necessarily with a lowercase letter – see I.6.3.1.8), then the author and the year, then the original generic name, separated by a comma or enclosed in brackets; it is best to enclose it in square brackets so as not to be confused with the name of the subgenus and be able to indicate in parentheses the original name of the subgenus. In short form, basionym can be given without an author and a year.

For example, the same species appears in the literature under the binary names Ephemera mutica Linnaeus 1758, Baetis muticus (Linnaeus 1758), Nigrobaetis muticus (Linnaeus 1758), Takobia mutica (Linnaeus 1758), and Alainites muticus (Linnaeus 1758), depending on how widely do certain authors understand the genera Ephemera, Baetis, Nigrobaetis, Takobia, and Alainites. The basionym of this name can be written as «mutica Linnaeus 1758 [Ephemera]» or simply «mutica [Ephemera]».

I.6.4.2. Basal format of typified names

In the rank-based typified nomenclature, the name of the suprageneric taxon is formed from the generic name by changing the end according to the rank of the taxon; the choice of the generic name is uniquely determined by the rules of the corresponding code (see I.6.3.1), and the choice of the rank of the taxon, and, accordingly, the end of the name, is arbitrary (see I.5.4.2). If we isolate from such a name that part of it that is uniquely determined by the rules of the code, we will get the name in the basal format. The name in the basal format can be written as follows: the generic name, the oldest for the taxon (with a capital letter, but not in italics, because in this case it is not the name of the genus or subgenus); slash (or other symbol); letter f or g indicating the rules of the code that give priority to a generic name. If the priority is established on the basis of authorship of the names of the genus group, then after the slash the letter g is written (from the word genus). If the priority is established on the basis of authorship of the names of the family group, then after the slash the letter f is written (from the word familia – family).

For example, for a taxon that unites all mayflies, the senior generic name is Ephemera Linnaeus 1758, so the name of the mayfly in the basic format can be written as Ephemera/g. For the same taxon, the senior name of the family group is Ephemerinae Latreille 1810, formed from the same generic name Ephemera; therefore, the name of the mayfly in the basic format can also be written as Ephemera/f. These two names can be combined by writing them as Ephemera/fg. The authorship of such a name in the basic format can be indicated as follows: Ephemera/fg [f: Ephemerinae Latreille 1810; g: Ephemera Linnaeus 1758], or shorter: Ephemera/fg [f:1810; g:1758], because in order to choose the correct name, you only need to know the date of publication, which provides the availability of the name.

If the senior generic names selected according to the rules for the genus group and according to the rules for the family group do not coincide, in the basic format of the name, you can specify two generic names with the corresponding letters f and g through the equal sign.

For example, for a taxon uniting cockroaches and praying mantises, the senior generic name is Blatta Linnaeus 1758, and the senior family-group name is Mantides Latreille 1802, derived from the generic name Mantis Linnaeus 1767. The name of this taxon in the basic format can be written as Mantis/f=Blatta/g; its authorship can be indicated as follows: Mantis/f=Blatta/g [f: Mantides Latreille 1802; g: Blatta Linnaeus 1758], or shortly: Mantis/f=Blatta/g [f:1802; g:1758].

A name in the basic format is not an unambiguous name for a particular taxon, because several taxa nested in each other have the same name in the basic format. To transform a name in the basic format into the name of a concrete taxon, it can be made either rank-based or hierarchical. In the first case, the ending of the generic name is replaced by a suffix and ending corresponding to the absolute rank (see I.6.3.1 and I.6.3.2), in the second case, the number corresponding to the relative rank in the accepted classification is added to the name in the basic format (see I.6.4.3).

I.6.4.3. Hierarchical name

The hierarchy-based, or hierarchical name (nomen hierarchicum) consists of a name in basal format (see I.6.4.2) and a number from 1 to higher. Number 1 is attached to the taxon which in the given hierarchical classification is the largest (highest). Subordinated taxa with the same name in basic format are numbered according to their order of subordination in such a way that the smaller (lower) is the taxon, the higher is the number.

The taxa with the same oldest generic name are numbered from the highest to the lowest, not vice versa, because the highest one can be easily identified based on priority, while splitting of the taxa can be unlimited.

Fig. 1.9 provides an example of how hierarchy-based names are generated. Let's assume we have attributed generic rank to a supraspecific taxon (as there is no restrictions on ranking, we may assign such rank to any taxon, however large or small, provided it includes at least one formal species). Then, based on ICZN rules for the genus-group (see I.6.3.1.4), we shall decide which generic name is valid for this taxon; in the example on Fig. 1.9 this will be Habrophlebia. This generic name becomes the base for the hierarchy-based name. We add to it the slash and a «g», which means the name is chosen under genus-group coordination rules; it give us Habrophlebia/g. A classification may include several hierarchically subordinated taxa, each of which, if assigned generic rank, will have the same name in basal format; the names will differ in their numbers. To start numbering we identify the highest (i.e. the largest) taxon to which such generic name may be applied; this taxon will get number one. In our example the highest taxon whose oldest generic name is Habrophlebia gets the hierarchy-based name Habrophlebia/g1. No taxon whose rank is higher than that of Habrophlebia/g1 can bear the name Habrophlebia, because such taxon would include not only the type species of the name Habrophlebia Eaton 1881 (which is Ephemera fusca Curtis 1834) but also the type species of an older generic name Leptophlebia Westwood 1840 (which is Ephemera vespertina Linnaeus 1768), so if we assign that taxon generic rank its name will be Leptophlebia, not Habrophlebia. All subordinated taxa having the same generic name get consecutive numbers, starting from the highest one, in such a way that the larger is the number, the lower is the rank. In our example Habrophlebia/g1 is divided into Habrophlebia/g2 and Habroleptoides/g1; Habrophlebia/g2 is divided into Habrophlebia/g3 and Hesperaphlebia/g1, because the names Habroleptoides Schoenemund 1929 and Hesperaphlebia Peters 1979 are younger than the name Habrophlebia.

Using this method and basing on genus-group priority rules alone, one can assign unique hierarchy-based names to all taxa within a classification. The names in basal format and their corresponding hierarchical names can be supplemented with family group names.

In this case the oldest family-group name derived from the generic name Habrophlebia, is Habrophlebiinae Kluge 1994; this name is younger than the oldest name derived from the generic name Leptophlebia – Leptophlebini Banks 1900; there are no family-group names derived from Habroleptoides or Hesperaphlebia. Thus, instead of the hierarchical names Habrophlebia/g1, Habrophlebia/g2 and Habrophlebia/g3, we can indicate more complete hierarchical names Habrophlebia/fg1, Habrophlebia/fg2 and Habrophlebia/fg3.

Fig. 1.9. Example of forming of hierarchical names in one of the mayfly taxa. Species are denoted by dots, supra-species taxa are denoted by ellipses.

If the generic names are identical but the numbers are not, we insert into the hierarchy-based name both numbers with their respective letters, separated by an «=» without spaces; if the generic names are not identical we write down both generic names (separated by an «=» without spaces) with their respective letters and numbers.

For example, there is a taxon that includes type species of two generic names: Caenis Stephens 1835 and Brachycercus Curtis 1834, of which the latter is older; however, the oldest family-group name derived from the name Caenis – Caenidae Newman 1853 is older than the oldest family-group name derived from Brachycercus – Brachycercidae Lestage 1924. The taxon including both type species will have the hierarchy-based name Caenis/f1=Brachycercus/g1. Such spelling means that under ICZN rules, if this taxon is assigned genus-group rank its name will be Brachycercus, while if assigned family-group rank its name should be derived from the generic name Caenis. One of subordinated taxa within Caenis/f1=Brachycercus/g1 also includes both type species, and its hierarchy-based name will be Caenis/f2=Brachycercus/g2. In rank-based nomenclature this taxon also can be either named Brachycercus or get a typified name derived from Caenis, depending on whether we consider it a genus-group or a family-group taxon. This taxon, in turn, contains two taxa: one including the type species of the generic name Caenis, and another – the type species of the generic name Brachycercus. The hierarchy-based names of these taxa will be Caenis/f3=g1 and Brachycercus/f1=g3, respectively. Hierarchy of these taxa looks as follows:

When classification changes, numbering in hierarchy-based names also shifts, so that in different classifications taxa of the same circumscription may have different names, while taxa of different circumscriptions may be named identically. Hierarchy-based and rank-based nomenclatures share such disadvantage, only circumscription-based nomenclature (see below) is free of it. The important benefit of hierarchy-based nomenclature is that the names shift only if there are changes in the classification, i.e. if the subordination of taxa is modified, while in rank-based nomenclature names change with any rank shift as well. In contrast to rank changes, always purely discretional, classification changes are always based on evidence and can be discussed.

If a hierarchy-based name is used, it may be helpful to provide details on how taxa are arranged in this classification, as a comment on the name's number. This can be done when the name is first mentioned, listing (in parentheses) generic names of closest excluded taxa (using «sine», Latin for «without») and those of directly subordinated taxa (using «incl.» – incluso, including).

For the names from the above example such comments can be given as follows:

Leptophlebia/fg1 (incl. Calliarcys, Habrophlebia, Atalophlebia);

Habrophlebia/fg1 (incl. Habroleptoides);

Habrophlebia/fg2 (sine Habroleptoides; incl. Hesperaphlebia);

Habrophlebia/fg3 (sine Hesperaphlebia).

Hierarchy-based names formed from one and the same name Scarabaeus are given in Table I.7.

Table I.7. Hierarchical names of some taxa considered in this book. Numbers referring to the taxa with senior generic name Scarabaeus are marked by red; number of ciphers marked in the left column is equal to the number in the corresponding hierarchical name.

|

through numeration of the taxa beginning from the highest among the taxa whose senior generic name is Scarabaeus |

hierarchical names |

circumscriptional names |

numeration of

the same taxa used in chapters |

|

1. |

Pediculus/f1=Scarabaeus/g1 |

Mandibulata |

IV-1.3.3 |

|

1.1. |

Cancer/fg1 |

Eucrustacea |

IV-1.3.3.1 |

|

1.2. |

Pediculus/f2=Scarabaeus/g2 |

Atelocerata |

IV-1.3.3.2 |

|

1.2.1. |

Julus/f1=Scolopendra/g1 |

Myriapoda |

V-1 |

|

1.2.2. |

Pediculus/f3=Scarabaeus/g3 |

Hexapoda |

VI-1 |

|

1.2.2.1. |

Podura/fg1 |

Entognatha |

VI-1.1 |

|

1.2.2.2. |

Pediculus/f4=Scarabaeus/g4 |

Amyocerata |

VI-1.2 |

|

1.2.2.2.1. |

Lepisma/fg1 |

Triplura |

VI-1.2.1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2. |

Pediculus/f5=Scarabaeus/g5 |

Pterygota |

VII-1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.1. |

Ephemera/fg1 |

Ephemeroptera |

VII-1.1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2. |

Pediculus/f6=Scarabaeus/g6 |

Metapterygota |

VII-1.2 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.1. |

Libellula/fg1 |

Odonata |

VII-1.2.1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2. |

Pediculus/f7=Scarabaeus/g7 |

Neoptera |

VIII-1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.1. |

Embia/fg1 |

Idioprothoraca |

VIII-1.1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.2. |

Gryllus/f1=Forficula/g1 |

Rhipineoptera |

VIII-1.2 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3. |

Pediculus/f8=Scarabaeus/g8 |

Eumetabola |

VIII-1.3 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.1. |

Pediculus/f9=Cicada/g1 |

Parametabola |

IX-1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2. |

Scarabaeus/f1=g9 |

Metabola |

X-1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.1. |

Scarabaeus/f2=g10 |

Elytrophora |

X-1.1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.1.1. |

Scarabaeus/f3=g11 |

Eleuterata |

X-1.1.1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.1.1.1. |

Cupes/fg1 |

Archostemata |

1. |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.1.1.2. |

Carabus/f1=Cicindela/g1

|

Adephaga |

2. |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.1.1.3. |

Scarabaeus/f4=g12 |

Polyphaga

s.l. |

3. |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.1.1.3.1. |

Sphaerius/fg1 |

Myxophaga |

3.1 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.1.1.3.2. |

Scarabaeus/f5=g13 |

Polyphaga

s.str. |

3.2. |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.1.2. |

Stylops/f1=Xenos/g1 |

Strepsiptera |

X-1.1.2 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.2. |

Myrmeleon/f1=Hemerobius/g1 |

Neuropteroidea |

X-1.2 |

|

1.2.2.2.2.2.2.3.2.3. |

Papilio/fg1 |

Mecopteriformia |

X-1.3

|

I.6.4.4. Priority of genus- and family-group names

Here it is necessary to comment on the origin of the oldest names of the genus group and family group.

Genus group. The oldest name of the genus group in zoology is Araneus Clerck 1758: according to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, the book by Clerk about spiders of Sweden (Clerck S. «Svenska spidlar», or «Aranei svecici»), actually published in 1757, is conditionally considered published in 1758 but prior the first of January of this year; due to this, the species names of spiders contained in it are considered available and having priority over the names given by Linnaeus (see I.6.3.1.2). Also, according to the decision by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (Direction 104, 1959), it is conditionally considered that this book contains the genus-group name Araneus Clerck 1758, which takes priority over the name Aranea Linnaeus 1758.